Last month, the official newspaper of the Communist Party of China warned that Beijing could soon stop exporting rare earths to the US.

The threat came ahead of an increase in US tariffs on $200 billion in Chinese goods that went into effect and the blacklisting of Chinese telecom giant Huawei by President Donald Trump.

Considering how critical rare earths are in modern society – used in everything from mobile phones and electric motors through to pool cleaner and lighter flints – it’s easy to see why this threat shook the market, including one of the most technologically demanding industries on the planet, the military.

According to a US Department of Defence study, the US defence sector alone consumes 500 tonnes a year of rare earth elements. In fact, just one F-35 Lightning II aircraft requires well over 400kg of rare earth materials, according to a 2013 report from the US Congressional Research Service.

But this flexing of trade-related muscle is not without precedent.

China cut off exports of rare earths to Japan in 2010 when the two governments were in dispute over ownership of islands east of Taiwan.

The move prompted the Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corp. – a government agency – to issue a loan to prop up the development of WA’s Lynas Corporation.

According to Bloomberg’s David Fickling, the first loan was issued at an interest rate of around 3 per cent. Putting that into context, Fortescue Metals Group, the world’s fourth largest iron-ore producer, had to pay as much as 8.25 per cent at the same time for its borrowings in the US junk bond market.

Lynas is the only significant producer of rare earths outside China, which Managing Director Amanda Lacaze says put it in a “very special position”.

Despite the name, rare earths aren’t that rare. One element, cerium, which is used to polish smartphone touchscreens, is 15,000 times more abundant than gold. However, the elements are typically dispersed and not often found in concentrated deposits which makes Lynas’ Mount Weld resource a rarity.

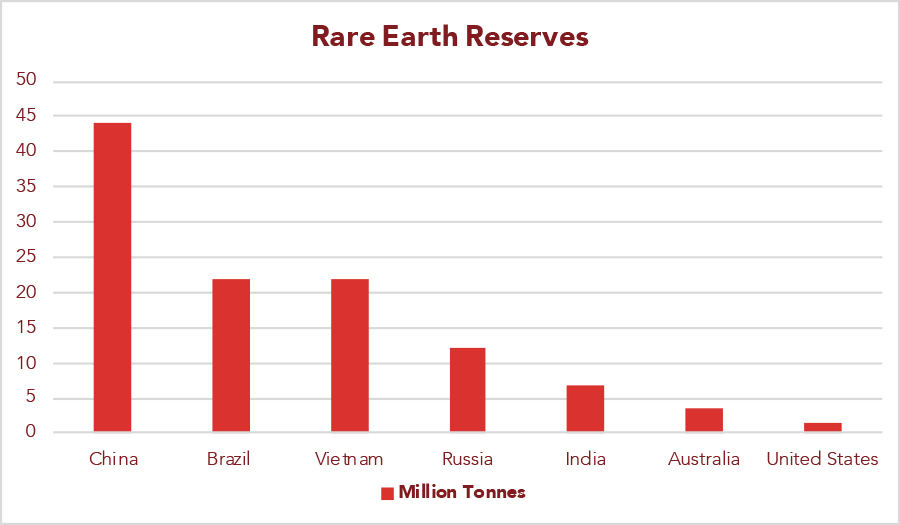

While Australia was the second-largest rare earth mining country in 2018 at 20,000 tonnes of production, it has only the sixth most significant reserves in the world.

Unsurprisingly, China has the largest reserves of rare earth minerals at 44 million tonnes. The country was also the world’s leading rare earths producer in 2018 by a long shot, putting out 120,000 tonnes.

China’s dominance is not just due to its rich endowment, but also by design.

Xu Guangxian, considered the father of the Chinese rare earth industry, created the State Key Laboratory of Rare Earth Materials Chemistry and Applications at the Peking University in the early 80s after returning from studying at Columbia University.

The chemist went on to advise the Government to adopt export quotas because he saw the potential rare earths had in the technology sector and wanted to keep them within China.

Even Deng Xiaoping, the Paramount Leader of the People’s Republic of China from 1978 to 1992, had an opinion about the elements, saying in a speech in 1992 “that the Middle East has its oil, China has rare earths”.

It is not just raw material supply that is of critical importance for the US, it is the entire rare earth supply chain.

A paper released in early June by the US Department of Commerce, a Federal Strategy to Ensure Secure and Reliable Supplies of Critical Minerals, states that increasing mining without increasing processing and manufacturing capabilities simply moves the source of economic and national security risk down the supply chain.

An example of this is rare earth-based permanent magnets. Despite increasing mining efforts, the US does not have the capability to separate and process rare earth concentrate, let alone the value-adding manufacturing to turn those minerals into the end product.

As Australian industry advisor Dudley Kingsnorth puts it: “China and rare earths are a bit like France and wine — France will sell you the bottle of wine, but it doesn’t really want to sell you the grapes.”

The Managing Director of Lynas, Amanda Lacaze tends to agree, saying that China had committed to cease rare earth exports by 2025, so it could monopolise the downstream processing of the commodities, the jobs it would create and capture the value-adding involved with exporting electric motors and cars.

Speaking at a WA Mining Club lunch, Ms Lacaze said that the United States and the rest of the Western world has been on the “heroin drip” of cheap rare earths for some time, which has left them exposed.

Much like in 2010, the increasing rhetoric around rare earths is creating an opportunity for Lynas once again, including the construction of a rare earth separation facility in the US for which the Company signed a memorandum of understanding with Texas-based Blue Line Corp in May this year.

According to Ms Lacaze, Lynas has competitive advantages with its “world-best” resource at Mount Weld near Laverton, its market position as the only producer outside China and the intellectual property it had developed in mining and processing rare earths.

“China has low labour costs, the US has scale, we have smarts,” she said at the mining club lunch.

“It impresses me daily the sorts of things that the people in our business can do.

“This is why it’s exciting today, this is why we have an opportunity to do it today differently from the way that we have done it before.”

The Company is aiming to increase Mount Weld’s production to 10,500 tonnes per year of neodymium-praseodymium products by 2025, up from 5,444 tonnes in the 2018 fiscal year.

The only immediate hurdle facing the Company are regulatory setbacks at the Lynas Advanced Materials Plant in Kuantan, Malaysia. The plant – one of the largest and most modern rare earths separation plants in the world – treats concentrate from Mount Weld and produces separated Rare Earths Oxide (REO) products.

The plant, which hires around 600 locals, has been making news for its hot tailings, with the Malaysian Government yet to issue the Company with a new operating licence.

While the plant is coming under increasing scrutiny, Ms Lacaze is adamant that processing rare earths is not a dirty business saying that it is not dissimilar to any other industrial process.

“Rare earths naturally occur in an environment that has low levels of radioactivity,” she said.

“The processing of rare earths does not activate, concentrate or in any way alter that naturally occurring low-level radioactivity in the ore.”

In a coup for WA, Lynas will set up cracking and leaching operations at either its Mount Weld mine or in Kalgoorlie to extract low-grade radioactive waste from its rare earths before they are shipped to Malaysia.

The move is aimed at securing the future of Lynas’ $1 billion plant in Malaysia at a cost of $500 million.

While the Company is geo-politically important, you still have to run it well, according to Ms Lacaze.

“As a publicly listed company, investors are going to make decisions on your access to capital,” she said.

Considering how the Company has been making headlines with a potential takeover bid by Wesfarmers, it seems to be making all the right moves.